Written by Diane Krieger | Photos by Vincent Rios

He was born, after all, in a displaced persons camp in Wiesbaden, Germany—the child of traumatized concentration camp survivors. The shtetls his Polish Jewish parents came from had been wiped off the map.

There was no going back, so Harry and Zelda Gelbart moved forward. They affirmatively chose happiness, resettled in Brooklyn, New York, and had two more babies. Harry supported the family as a tailor. Zelda raised the kids.

They never spoke of the Holocaust, but it surely colored their lives—in the Yiddish spoken around the kitchen table and, later in the career choices of two of their children. Both Moe and his sister Mia became psychologists.

Looking back, Gelbart reflects, there were similarities between his and his father’s professions: both were in the business of making alterations. Harry Gelbart adjusted sleeve lengths. Moe Gelbart readjusted troubled minds.

Though his role as director of behavioral health only started in October, Gelbart is no newcomer to Torrance Memorial. His connection goes way back to 1978— the year he earned his doctorate degree in psychology from USC.

He came to the profession a bit circuitously. Gelbart had studied economics at Brooklyn College, but his heart just wasn’t in it. So he went to work as an English teacher at a Brooklyn junior high school. A remedial reading class exposed him to educational psychologists and social workers who showed him new ways to reach troubled teens. Intrigued, he enrolled in a master of educational psychology program at City College of New York. From there, he applied to the doctoral program at USC.

Gelbart and his wife, Debbi, moved to California in 1974. It was a time when USC’s most famous professor was Leo Buscaglia, aka “Dr. Love.” Gelbart himself was trained in “existential-humanistic psychology”—a school of thought focused less on treating disorders than on showing patients how to lead richer, fuller lives.

“It’s a really good framework for understanding people—how they think, make choices, all the things they do,” says Gelbart, now a leader in the South Bay mental health community for more than 40 years. “It helped me understand myself as much as become a good psychologist.”

He began practice as a licensed marriage and family therapist in 1976, moonlighting while he worked on his doctorate. He counseled juvenile offenders in a Redondo Beach diversion program. He was a police psychologist with the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department.

He was running a chronic pain program at a Redondo Beach rehab center when Torrance Memorial tapped him to direct its fledgling outpatient pain management unit. It was the beginning of a 42-year relationship that’s still going strong.

Along the way, Gelbart built two large mental health private practices: PsychCare Alliance, a network of 400 practitioners that was dissolved in 1999; and Gelbart and Associates, until recently the South Bay’s largest psychotherapy group practice, with 40 clinicians spread across offices in Redondo Beach, Torrance and Palos Verdes. Last year, Gelbart sold that practice to Community Psychiatry so he could devote himself full-time to Torrance Memorial.

At 72, he now only sees a limited number of private patients. He’s happy to pass the clinical torch to younger psychotherapists, including his daughter Jamie, a licensed marriage and family therapist.

His new job at Torrance Memorial cements a role Gelbart has long played informally—seeing to the emotional well-being of the hospital’s 4,000-person workforce and making sure psychological services are readily available to patients and their families. “I love working with the hospital,” he says. “Whenever they needed something, I tried to help them develop or get it. I’ve tried to be a resource to the hospital for 40 years.”

Having directed Torrance Memorial’s pain program through the mid-1980s, Gelbart spent a decade as staff psychologist with the hospital’s now-disbanded inpatient psychiatric unit. In 1992, he added a new role as founding director of the Thelma McMillen Recovery Center.

Affectionately known as “Thelma,” the intensive outpatient alcohol and drug treatment center works full-time with as many as 140 adult and teen patients. During the pandemic, the program is fully and completely functioning remotely. Gelbart remains McMillen Center’s executive director alongside his new role as Torrance Memorial’s director of behavioral health.

He has helped develop many other programs over the decades. One innovative program provides a psychiatrist in the emergency room two hours a day via telehealth, conducting patient mental health evaluations. In another project, Gelbart helped set up psychiatrists to deliver three hours a day of on-site services to all hospital departments.

On the workforce side, he oversees two employee benefits programs providing free counseling sessions to any Torrance Memorial staff or family member who needs them. Responding to unprecedented workplace stresses brought on by the pandemic, Gelbart has recently helped implement a coronavirus support group just for doctors.

In his new role, Gelbart is working on several projects including increasing community mental health services supporting women’s reproductive mental health. In collaboration with Deepjot Singh, MD, of the OB-GYN department, that service will provide better access to psychotherapy resources for patients dealing with miscarriage, postpartum depression or other pregnancy-related stress.

Another project he is collaborating on with several physicians is attempting to integrate behavioral health into Torrance Memorial’s primary care offices, allowing patients quicker access to psychological and psychiatric care.

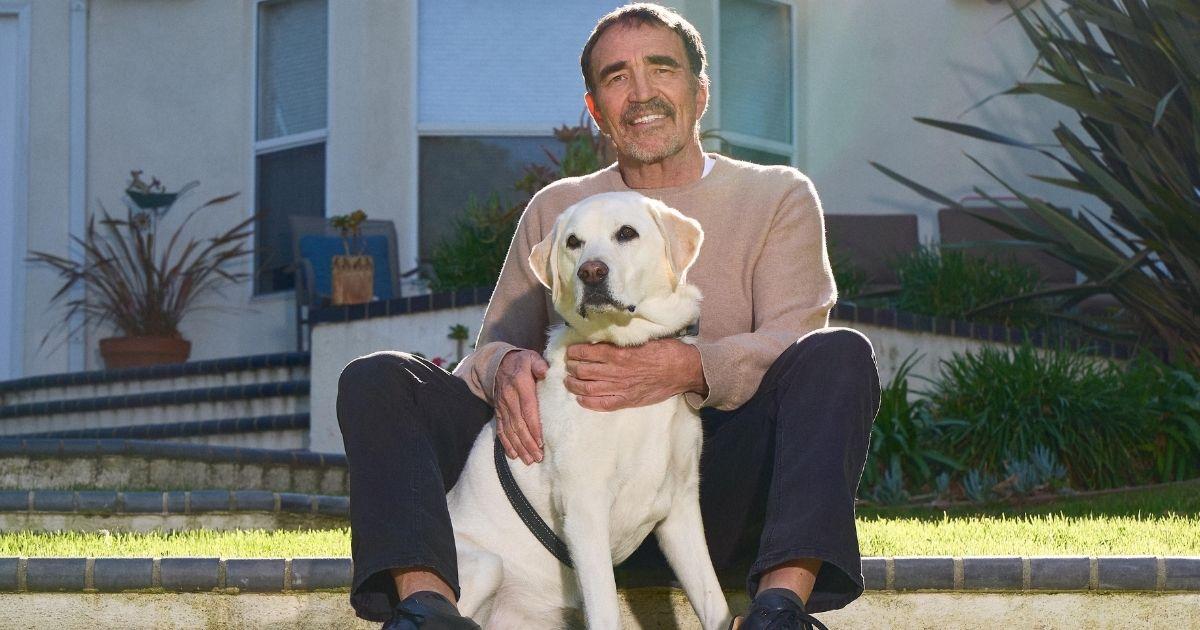

Since the pandemic started, Gelbart has also been one of the hospital’s mental health spokespersons. Through appearances on television and quotes in newspaper interviews, he is a calming voice of resilience for the South Bay community. He also writes regularly for Torrance Memorial’s blog. He owns a therapy dog, a yellow lab named Sophie, who provides therapy to kids in school environments.

With all these connections, Gelbart calls the decision to sell his practice and become director of behavioral health a natural course to take at this time in his life. “Torrance Memorial has been a big part of my life,” he says wistfully. “I know everybody at the hospital. These are my friends. These are people who come to my house parties, and I go to their kids’ weddings.

About those parties … they’re the stuff of South Bay legend. Every few years, Gelbart throws a blowout Woodstock revival at his Rolling Hills Estates home. He was one of the 400,000 free spirits who descended on Yasgur’s dairy farm for the iconic 1969 rock festival, and he periodically likes to recreate the scene with 150 hippy-costumed friends.

He’s also famous for his pizza parties, firing up the backyard wood-burning oven and inviting guests to improvise with homemade dough and platters of exotic toppings. Gelbart’s own signature pizza is good old-fashioned margherita. In another long-standing tradition, for 25 years Gelbart has enjoyed a weekly poker game with the same group of friends—all New York transplants like himself.

Gelbart is now a grandfather, his home office filled with stuffed animals belonging to Emma, 4, and Nomi, 2. The girls live in West Los Angeles, but their parents, Josh and Sarah, take them to see their grandparents often.

Gelbart and Debbi will celebrate their 50th anniversary next year. An art teacher for three decades, she recently retired from the faculty of Rolling Hills Prep.

Looking back, Gelbart—in keeping with his early training in existential humanistic psychology—appreciates the rich, meaningful life he’s led. “I’ve had a good, long career. I’ve helped a lot of people. And if you ask me how I feel about the hospital, it’s like … this is where my loyalty lies. I’m so grateful to be here at this time in my career.”